De ontdekking

De totale geschiedenis van ontdekking is te lang om hier weer te geven, dus ik kan alleen enige conclusies geven.

Ik ontdekte de Diagonaal Methode in mei 2006 gedurende onderzoek naar de onnauwkeurigheid van de Regel van Derden. Ik moest weten waarom de Regel van Derden niet "werkte", iets dat ik een paar jaar daarvoor had ontdekt. Volkomen onverwacht vond ik een andere compositiemethode, die ik eerst de "Cirkel Methode" noemde en een paar dagen later de "Diagonaal Methode" Na jaren van onderzoek kwam ik tot de conclusie dat de Regel van Derden niet werkt omdat dit een theorie is - net als de Gulden Snede (in beeldende kunst) een theorie is - . Sommige mensen geloven in deze theorieën, maar het blijven theorieën, met andere woorden: ze werden niet ontdekt als daadwerkelijk bestaand in actuele kunstwerken. De Diagonaal Methode is ontdekt als werkelijk bestaande methode in concrete schilderijen en foto's, waarbij er niet werd geprobeerd om één of andere theorie te bevestigen. Dit maakt de Diagonaal Methode een ontdekking en geen theorie. Pas wanneer deze ontdekking publiekelijk gepresenteerd wordt, wordt het een "theorie". In het volgende gedeelte zal ik enkele fasen van de toelichten.

Ik ontdekte de Diagonaal Methode in mei 2006 gedurende onderzoek naar de onnauwkeurigheid van de Regel van Derden. Ik moest weten waarom de Regel van Derden niet "werkte", iets dat ik een paar jaar daarvoor had ontdekt. Volkomen onverwacht vond ik een andere compositiemethode, die ik eerst de "Cirkel Methode" noemde en een paar dagen later de "Diagonaal Methode" Na jaren van onderzoek kwam ik tot de conclusie dat de Regel van Derden niet werkt omdat dit een theorie is - net als de Gulden Snede (in beeldende kunst) een theorie is - . Sommige mensen geloven in deze theorieën, maar het blijven theorieën, met andere woorden: ze werden niet ontdekt als daadwerkelijk bestaand in actuele kunstwerken. De Diagonaal Methode is ontdekt als werkelijk bestaande methode in concrete schilderijen en foto's, waarbij er niet werd geprobeerd om één of andere theorie te bevestigen. Dit maakt de Diagonaal Methode een ontdekking en geen theorie. Pas wanneer deze ontdekking publiekelijk gepresenteerd wordt, wordt het een "theorie". In het volgende gedeelte zal ik enkele fasen van de toelichten.

|

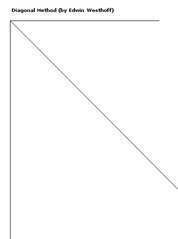

Vanwege de nauwkeurigheid van de DM is het noodzakelijk om de sheet exact op de hoeken van de afbeelding te plaatsen, met een nauwkeurigheid van 1/10 mm, als je een afbeelding wilt testen op de aanwezigheid van de DM.

Het is niet mogelijk om de DM te zien zonder deze testsheet, hoewel je met zeer veel ervaring hier een gevoel voor kunt ontwikkelen. Dan nog moet de testsheet uitwijzen of het klopt. Je kunt ook het gereedschap "Diagonaal" in Lightroom of Photoshop gebruiken natuurlijk. fig. 2. |

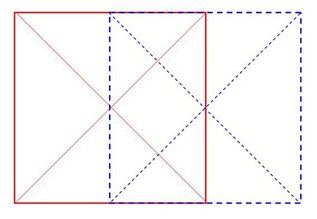

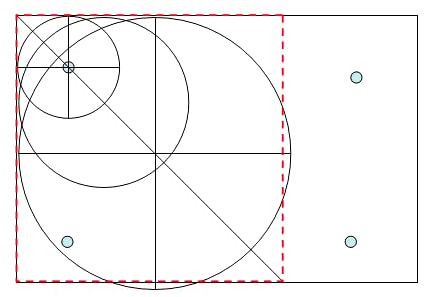

Het kleinbeeldkader is een rechthoek met een verhouding van 2:3. Binnen deze rechthoek kan je twee overlappende vierkanten (zie fig. 1).

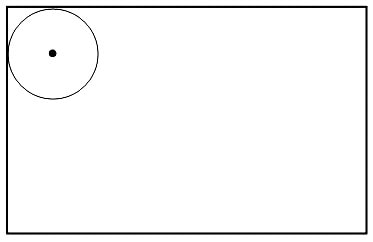

Ik ontdekte dat kunstenaars zoals Rembrandt, beroemde fotografen, maar ook amateurfotografen, vaak belangrijke details exact op de diagonalen plaatsten. OM dit te testen gebruikte ik een transparant sheet met een 90 graden hoek ene een bissectrice (zie fig. 2). Fig. 1. |

|

Belangrijke details liggen meestal exact op één van de Diagonalen, dus met afwijking van 0 mm op A4 formaat. Afwijkingen van 1 of 2 mm komen zelden voor. Precies deze nauwkeurigheid gaf de doorslag in de week van de ontdekking. Als de DM net zo onnauwkeurig was geweest als de Regel van Derden had ik al mijn onderzoek in de prullenbak gegooid en had nooit iemand er ooit van gehoord.

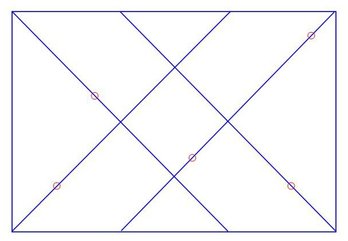

De cirkeltjes op de Diagonalen symboliseren mogelijke posities van details in een afbeelding (zie fig. 3). fig. 3 |

|

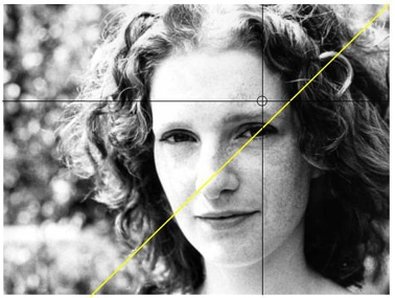

De letterlijk eerste afbeelding die ik testte was een portret van één van mijn cursisten (zie fig.4). Ik was verbaasd, niet te zeggen geschokt, te zien dat de Diagonaal exact door het midden van de pupil van het oog liep (gele lijn). De twee kruisende zwarte lijnen zijn van de Regel van Derden.

Na het testen van honderden schilderijen, tekeningen en foto's van beroemde kunstenaars en amateurs, zag ik dat bij relevante afbeeldingen - d.w.z. afbeeldingen die inhoudelijke belangrijke details kunnen bevatten zoals ogen - , dergelijke details precies op de bissectrices waren te vinden (die ik de "Diagonalen" noemde - met een hoofdletter om aan te geven dat het om de Diagonaal methode gaat en niet om de meetkundige diagonalen. fig. 4. |

Gedetailleerde uitleg van het experiment

under construction (onderstaande tekst moet nog vertaald worden)

Voor lezers die precies willen weten waar het experiment uit bestond:

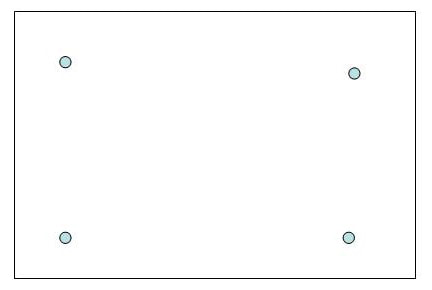

I drew (with the computer in Word) five rectangles with an exact 2:3 ratio (as is used in 35 mm photography) on 5 sheets of A4 paper. The reason for this was that, if the Rule of Thirds does not work, what would happen if I would place four dots in a rectangle, comparable with the four cross points of the Rule of Thirds, in an absolutely non-rational way, just by feeling or intuition?

I did this on the 5 sheets of paper, so I got 5 rectagles with 4 dots in each rectangle (fig. 1), somewhere in the four corners. I looked at these and I saw that the dots in the upper left corner were lying more or less on the same position, in all the five rectangles. I did not know what to do next. Thinking of the use of circles by Rudolf Arnheim, I made a circle on a transparancy and placed the centre of the circle on the dot in the upper left corner. To my surprise I saw that this dot was lying as far from the upper frame line as from the left frame line (fig. 2). Directly hereafter I tested a photograph made by a student (see the photo above), and was shocked to see that, - when placing the circle so that it would fit exactly in the corner - , the centre of the circle was exactly on the left eye of the girl (the right eye for the viewer).Then I tested dozens of famous paintings and famous photographs and was again shocked to see that very important details, concerning the content of the art works, were on the centre of the circle. I called this then "The Circle Method."

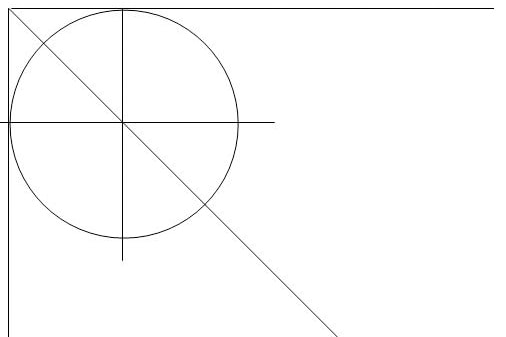

During the writing of a chapter about this discovery in my new book about composition for my classes, I continued with my research and discovered that the centre of the circle was at the same time lying on the bisection line of each corner of the rectangle (or the frame of a photograph) (fig. 3). This meant that the bisection lines were at the same time the (mathematical) diagonals of the two overlapping squares in the rectangle (fig. 4).

So I changed the name in "The Diagonal Method". Actually I did not know then that this dividing line was called the "bisection line". A student of mine said this to me. This would mean that I could rename the discovery again and call it "The Bisection Method". But by then Adobe had already implemented my discovery in Lightroom version 1.1., naming it "Diagonal", so I could not rename it again. So it will always be called "The Diagonal Method".

under construction (onderstaande tekst moet nog vertaald worden)

Voor lezers die precies willen weten waar het experiment uit bestond:

I drew (with the computer in Word) five rectangles with an exact 2:3 ratio (as is used in 35 mm photography) on 5 sheets of A4 paper. The reason for this was that, if the Rule of Thirds does not work, what would happen if I would place four dots in a rectangle, comparable with the four cross points of the Rule of Thirds, in an absolutely non-rational way, just by feeling or intuition?

I did this on the 5 sheets of paper, so I got 5 rectagles with 4 dots in each rectangle (fig. 1), somewhere in the four corners. I looked at these and I saw that the dots in the upper left corner were lying more or less on the same position, in all the five rectangles. I did not know what to do next. Thinking of the use of circles by Rudolf Arnheim, I made a circle on a transparancy and placed the centre of the circle on the dot in the upper left corner. To my surprise I saw that this dot was lying as far from the upper frame line as from the left frame line (fig. 2). Directly hereafter I tested a photograph made by a student (see the photo above), and was shocked to see that, - when placing the circle so that it would fit exactly in the corner - , the centre of the circle was exactly on the left eye of the girl (the right eye for the viewer).Then I tested dozens of famous paintings and famous photographs and was again shocked to see that very important details, concerning the content of the art works, were on the centre of the circle. I called this then "The Circle Method."

During the writing of a chapter about this discovery in my new book about composition for my classes, I continued with my research and discovered that the centre of the circle was at the same time lying on the bisection line of each corner of the rectangle (or the frame of a photograph) (fig. 3). This meant that the bisection lines were at the same time the (mathematical) diagonals of the two overlapping squares in the rectangle (fig. 4).

So I changed the name in "The Diagonal Method". Actually I did not know then that this dividing line was called the "bisection line". A student of mine said this to me. This would mean that I could rename the discovery again and call it "The Bisection Method". But by then Adobe had already implemented my discovery in Lightroom version 1.1., naming it "Diagonal", so I could not rename it again. So it will always be called "The Diagonal Method".